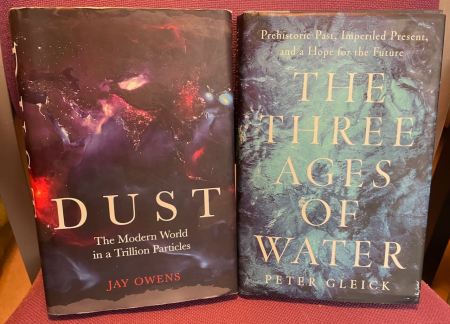

Friends, I have recently read two books that have caused me to re-evaluate – in the words of Peter Gleick – the true value of water. The first book, Dust, considers the role of dust in human culture. And the second, The Three Ages of Water, describes the critical importance of fresh water for all life on Earth. Partly to help me recall the contents, I thought I would write a précis of the two books, and I hopefully you will find this of interest too.

Dust

Dust may seem an odd topic for a book, but it in fact dust is an intrinsic part of the natural world and plays an outsize role in many geophysical processes. As materials break down, they turn into small and smaller particles and at some point – below around about a tenth of a millimetre or so – we somehow lose consciousness of them as individual particles. But the materials are still there. Crucially, when not bound by water, particles of this size are small enough to be lifted by the wind and held aloft.

Jay Owens begins her assessment of the significance of dust in her own flat as she reflects on the astonishing amount of otherwise invisible dust made visible in the beams of sunlight. This is the start of a world-wide journey.

She first revisits the origin of the concept of ‘dusting’ – a task which arose from combination of the appalling particulate pollution from coal burning, and the development of consumer goods which needed to be displayed. She argues that the idea of household cleaning as “women’s work” led to the oppression of women throughout the 19th and 20th Centuries.

She visits Owen’s Valley, California where in the 1920’s entrepreneurs from Los Angeles acquired – through techniques of dubious legality – water rights that underpinned the growth of Los Angeles and led to the destruction of Owen’s lake, which became a source of toxic dust, and led to the desolation of a fertile valley. And she visits the land at the heart of the creation of the dustbowl in the US in the 1930’s.

Likewise she visits the Aral Sea where in the 1960’s soviet planners re-directed the sources that fed the Aral Sea in order to grow cotton. Since then the sea has all but disappeared, leading to toxic dust storms that have led to the desertification of a once fertile ecosystem.

Click on image for a larger version. USGS Landsat images of the Aral Sea in 1992 and 2020. Even in 1990 the sea, once the 4th largest freshwater lake on Earth, had already undergone significant contraction.

She visits the areas around atomic bomb test sites and investigates the lasting impact of the clouds of invisible radioactive dust that spread across the USA from the explosions.

Click on Image for a larger version. From the Downwinders Website, this graph shows the dose of radioactive Iodine -131 at locations across the US as a result of dust particles from atomic bomb tests.

And she visits Greenland to see the effect of particles of black carbon on the melting of the ice sheet.

Click on Image for a larger version. The upper image from the American Museum of Natural History shows a section of an ice core from the Greenland Ice sheet. The yearly bands are clearly visible. The lower graph shows analysis of such ice cores revealing the amount of black carbon dust deposited year by year over the last 800 years.

Throughout all her travels, Jay Owens emphasises the outsize role that tiny particles of dust play, and notes that somehow it always the less powerful groups in society that suffer. Although her writing is polemical at times, I feel that the book has nonetheless raised my consciousness of dust. Previously I had thought of dust as being incidental or peripheral, but in fact, if you look for it, dust is everywhere.

Water

We all know that water is important, but Peter Gleick’s aim in writing this book is to urge is to see the true value of water.

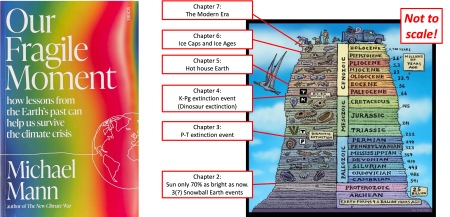

In the first age of water, he discusses the role of water in the prehistory of the solar system, our planet, and the development of life, and leads us eventually to the critical role of water in the first civilisations that we know of, circa 5,000 BC.

What I had not fully appreciated is the profound extent to which control of water – via the construction of dams and irrigation structures – was at the base of all of the activities of these civilisations. And that loss of control – either via floods or drought or conflict – led to the collapse of societies, over and over again.

The second age of water – the age in which we are now living – is the age in which we ‘mastered’ fresh water. We can now control the flow of water from mountains to the sea, and we can ‘mine’ water from deep underground. And we know how to create potable water almost anywhere on Earth. And yet after perhaps 150 years of mastery, we find ourselves in a very difficult place.

Most critically, despite the UN declaring water to be a fundamental human right – with a nominal target of 50 litres per day – millions of people on Earth still lack basic facilities for drinking and hygiene.

Click on Image for a larger version. Based on weekly meter readings, the graph shows the household usage of water for myself and my wife is on average around 100 litres per person per day.

Additionally, and I don’t need to tell this to UK readers, many of our rivers and water courses are polluted to the point where ecosystems have been damaged.

Perhaps the defining feature of the second age of water is that we have treated water as being “ours” and considered any water which is not captured or used to be wasted or ‘lost’.

And worldwide we have mined “fossil” water collected in aquifers over thousands of years to create agricultural systems that have flourished for a few decades, but which are – literally – unsustainable. If we run out of almost any other substance, we can find a substitute, but there is no substitute for water.

The third age of water is the age which Gleick believes we are entering, and age in which we truly value water as the unique element around which all ecosystems are constructed. Some features of this age are:

- Reduction of the amount of water that we use, domestically, industrially and agriculturally – but with no reduction in the utility we extract from the water.

- Valuing potable water for the wonderful product that it is and using ‘grey’ water for many of the functions for which we currently use potable water.

- Valuing the ecosystems within which all life exists, even to the point of giving rivers and ecosystems legal representation. Already, the US is removing dams to allow the slow re-building of natural water courses, and wetland restoration projects are underway world -wide.

I found the book by turns educational and inspiring. Although hearing of the phenomenal degradation left over from the second age of water, I feel that we have now universally accepted that it’s generally a bad thing when rivers catch fire. [Note added: Randy Newman wrote a song about one of the better known river fires]

As I was reading the book reports were unfolding of the appalling behaviour of Thames Water, the company that supplies my own water. And I was reminded that water is still of fundamental importance and that as in the civilisations of Early Mesopotamia, kingdoms could fail if water was not well-managed.

Water & Dust

As regular readers will know, I am personally immersed in issues around our Climate Crisis. And I try to avoid becoming too involved in our other ongoing ecological crises – things can get very depressing! But together these books have raised my consciousness without getting me down too much. The Three Ages of Water in particular sets out a very positive and achievable agenda for change.

The anomaly in the Earth’s temperature based only on thermometers in meteorological stations and excluding the oceans which cover about 70% of the Earth’s surface. The Daily Mail only draw your attention to a small fraction of the data – and they include monthly fluctuations which disguise the clear warming trend.

The anomaly in the Earth’s temperature based only on thermometers in meteorological stations and excluding the oceans which cover about 70% of the Earth’s surface. The Daily Mail only draw your attention to a small fraction of the data – and they include monthly fluctuations which disguise the clear warming trend.

The estimated change in the temperature of the air above the oceans and the land. The red line shows a smoothed version of the annual data with a 20-year window to reflect changes in climate rather than the internal fluctuations of the Earth’s complex weather systems. Notice that since 1980 , the smoothed line is essentially straight with a gradient of approximately 0.017 °C per year. Source: NASA-GISS: see article for details

The estimated change in the temperature of the air above the oceans and the land. The red line shows a smoothed version of the annual data with a 20-year window to reflect changes in climate rather than the internal fluctuations of the Earth’s complex weather systems. Notice that since 1980 , the smoothed line is essentially straight with a gradient of approximately 0.017 °C per year. Source: NASA-GISS: see article for details